Webinar Rewind: Episode 4

Just like all organisms in nature, brands must evolve to survive. But in today’s world, brand identity changes and logo evolutions can be cultural lightning rods—disliked by some, beloved by others, critiqued and discussed by all. It’s unavoidable. What matters is your approach: how you navigate design risk and shape an identity that allows a business to grow, be better understood and drive measurable impact.

Episode 4 of our webinar series, the case for design risk, reveals when to evolve, what it takes to design to break through in today's cluttered world, and how to activate and measure identity change so it becomes an operational lever for growth—well beyond the logo.

Highlights include:

- Build from what is authentic and true to the organization: The brand should be an embodiment of an organization and therefore needs to be authentic to itself. For this you need to understand and have insight into the core of the organization.

- Make decisions strategically, not subjectively: Taking a design risk is not guesswork or for risk’s sake. It’s structured, strategic, and grounded in truth.

- Get the CEO to own brand as a tool for transformation: The CEO owns the strategy, and brand is their tool to control the narrative.

- Narrate the why to turn skepticism into support: Brands that guide users through an authentic why — with narrative, not just visuals — turn skepticism into support.

- Designing a system, not a moment: Ensure change is about something bigger– not just a visual update.

Laura Schultz: Great. Hi, everyone! Welcome to the last episode of our 2025 webinar series. I'm happy to have you. We'll be talking about the case for design risk today. With that, I'll turn it over to our host, Jenifer and Lee. You guys take it away.

Jenifer Lehker: Sure. Yeah, thanks to everyone for joining us today. I'm Jenifer Laker, I'm a creative director based out of New York.

Lee Coomber: And I'm Lee Coomber, I'm the creative director responsible for the work in Europe and the Middle East. And, I've had the privilege to be working in branding for the last 30 years. Now, while I'm still learning all the time. I think that today we're going to go through what some people might already think are kind of universal truths, but I think hopefully bring a new perspective and slant on. For those who don't know, which I suspect there's not many of you out there, but we've just celebrated our 80th birthday, and over that time, Lippincott have had the privilege to build some of the most powerful household brands. And it's rare that actually you can walk down, particularly in the US, of course, you can't walk down the street without seeing Lippincott’s handiwork. While we're going to talk about design today. We have experience and expertise in lots of capabilities around How to build a winning brand, whether that’s unlocking opportunities that you may not know were there, or revitalizing the brand, or indeed marketing foundations, or inspiring and strengthening the employee engagement. There's many things that, go much broader than what we're going to talk about today.

But the question that we're going to hopefully explore with you is, why would you change in identity. And if you are, how would you think about risk? How would we reframe thinking about risk? And what can we do to make change a success? And then we can go into some questions and hopefully, hopefully there'll be some good ones.

So, again, if you're on this call, you probably are a believer in brand. I think it's unequivocal that a good brand is a good thing in terms of overall market value can be super helpful. There's a 5-13% value on that. And contribute… between 9% and 28% higher growth revenue. And if you take somebody, let's say, like Apple, which is worth $3.97 trillion when I looked last night. Their brand is worth 1 trillion of that. So, there is can be no argument that it is a good thing.

What we're going to talk about today is that I think design is a keystone in that. Design is the emotional building block from which all brand experiences are derived. So, it's absolutely critical that one gets that right. And in terms of when a brand changes, again, fabulous opportunity, I think. We may know this, but externally, it allows a brand to make strategic moves it might not otherwise have been able to do. It really demonstrates a commitment to progress. And it enables that leadership to tell their business story in a way that they don't get the opportunity otherwise. And it drives attention in a way that absolutely nothing else can for both good and bad internally, And perhaps even more powerful in the externally, is the catalyst that helps a change agenda to succeed. It's real proof to the employees that that leadership group is committed to progress and creates that pride and renewed engagement with… often with the business itself. So… and then as a side product, it can often be a really good driver in terms of cost efficiency as you look to redo things in new and more efficient ways.

Now that's the good news. Problem is, of course, that people don't like change, and that is particularly true of logo changes. Life around us moves fast enough, constant changes, and as a rule. Logos are not really meant to change, are they? They've been like that for 10, 20, 30 or even longer years. Logos are supposed to be a constant. We get very familiar with them, they help us make choices, simplify the world, They let us know what we want and how we want it. They symbolize the things that we subscribe to. So, when you change them. And in the way Gap, Jaguar, Cracker Barrel, and many others have found out, that can be hard, right? Because that change hasn't aligned with expectations. And often, maybe simply put, But people feel like they've had something taken away. Folks understood and trusted what that symbol stood for, and now they're confused, because you've changed it, and they don't understand why. And it's a really unhelpful and unwelcome disruption to something that somehow people feel very, very personal about. So, the question is why would you take the risk? Because of those dangers of getting it wrong. Jenifer, do you want to just talk through this piece?

Jenifer: The reason we can't just stop and stay where we are and avoid any criticism, if we take a look across history. Here we go. We see a pattern and a story for those who don't evolve and stay at the pace of change. Looking at this chart, looking at the original Forbes 100 companies, only one has survived wars and innovations, such as railways, radio, TV, internet. And we'll see what happens now that AI is becoming such a big innovation. And that it really tells a story of how companies have done staying at that pace of change. Lee, can you guess who the survivor is? The one remaining survivor after all these years?

Lee: The one remaining survivor is GE.

Jenifer: That's right, who has done an amazing job over the years of continually evolving their business. I mean, I feel like they're constantly in the news for re… Reorganizing their business. They've done a good job at, you know, keeping their brand feeling modern, which has enabled them to kind of stay at that pace of change. And who was the second-to-last survivor?

Lee: Second last was Kodak, and in fact, as you mentioned, GE is quite interesting, because they're always viewed as having a sort of a heritage brand. Interesting enough, they've changed it 11 times in that period. That's kind of almost every 13 years, so you do need to be on it.

Jenifer: Yeah. So if there's one shared trait among vital brands, it's action, and it's that drive to evolve. And everything needs to evolve at some point to survive. Which brings us to our overarching theme here today, that evolution is a necessity for living things. Nature has to adapt and, adapt to thrive. And design is a key component of any business evolution, for business to thrive. And so that's really kind of our overarching theme of today. The necessity to evolve and adapt, to take that risk.

So, there are a few requirements that really drive change those triggers that you can't ignore that are gonna, move you into considering an identity change. All of the identity changes typically fall into these buckets, whether it's an extraordinary event, which is a merger, an acquisition, a spin-off, or a catastrophic event.

Which are pretty rare. A strategic shift, which most evolutions fall into. This is when you know, it's a shift in story. There's been a shift in the positioning of a brand, or we're making a shift in how the position, sorry, the company is organized. This is how many of the businesses are going through a process of rebranding to meet the expectations of that strategic shift. Or the third one is a performance-based shift. The logo or the identity

Wasn't built to meet the needs of today's current place where it needs to live. It's not scalable. It doesn't live in today's digital marketplace. It needs to be optimized to work, as beautifully as it needs to, to live in the modern age. So these are kind of the three, identity changes that spark change today, and we'll go through some of those examples. But interestingly enough, sorry, if we go back really quickly, the pace of change is accelerating from what we see. We, we track this.

Every few years to see what the pace is, and it's accelerating. Within the last 10 years, 40% of the Fortune 500 have updated their identity. And then it's going even quicker, because in the last 5 years, 25% have updated their identity. So we see that pace of change just ramping up. And we expect that that's going to continue, just as the pace of change in general is getting faster and faster. So, just a few examples of an extraordinary event, and this includes about 18% of the identity changes over the Fortune 500 in the past 10 years.

An example of that would be Delta. When they were, moving in with Northwest Airlines and moving out of their, Chapter 11, they really needed to signal strength. They wanted to signal an emboldened expression, so coming out with a powerful red signal to signal that strength, was a way to really tell a fresh story, and come out even stronger. Another story, catastrophic events aren't very frequent. This is pretty rare, and you may not know this story of Ratner's. This is a story that came out of London, and we may have heard of this today, because they actually did have back in the 90s, about a thousand stores in the U.S, but very quickly, they went out of business because of one speech from the CEO.

Lee: That in about a course of a week, basically ran them out of business. We also have cherry decanter, it's cut glass, and it comes complete with 6 glasses on a silver-plated tray that your butler could, bring you in and serve you drinks on. And it's really only cost £4.95. People say to me, how can you sell this for such a low price? I say because it's total crafts. Oh, there's no point beating around the bush.

Jenifer: And he went on to say a few other disparaging things. So, it's not great when the CEO is, you know, knocking your own brand, but from that, again, they lost about the equivalent of about $2 billion today within a week of that speech. And after that, they transitioned to a completely new brand, Signet Jewelers, and that's why you've never heard of, likely never heard of Ratner's today.

The second bucket, a strategic shift, again, this is where the bulk of change falls into. 70% of the change within the last 10 years fell into this group. An example like Danaher, where they were looking to, really pull together their, powerful corporate brand bringing that to life in a bold way, really looking to stand that up, as it was unknown, and really looking to make that known, and known for a really innovative cutting-edge force in the future of science and technology, with a bold new identity, to something like Google, which was a bit more of a subtle shift, but an important shift to them that really reinforced this story of, we are approachable, we're taking a little bit more of a softer look to it.

To really, kind of fight against this look that we're a big behemoth or Goliath. To fight against some of the monopoly, story that was going on in the marketplace. So, it covers kind of a range of level of change, but all in kind of support of a strategic story. And then the last group is about performance, or thinking about optimization. And this is kind of the smallest bucket, but I think we expect that this is going to increase over time. And this is everything from, you know, a simplification of an identity, to a shift of color, to, you know, really optimize the weighting for legibility. But for MasterCard's case, it was removing the name, which was really seen as an initially risky move. To take the name out of the logo, but later seen as quite brilliant, because it really enabled the logo to work globally, beautifully, because it required no translation. And because their symbol is just so globally recognized, they have that ability to strip the name out and just go with the symbol. To something like Standard Charter, and Lee, this was one of your projects, you want to speak through that one?

Lee: Yeah, and it's interesting, sometimes these things coalesce. So, for Standard Chartered, if you ask the market.

Most people felt that it was sort of like your dad's bank. It wasn't a cutting-edge bank. But in fact, they'd invested billions in tech, and in fact, they had some of the best platforms in the world for delivering it, yet their identity just didn't work. So you have to change. You can't change it. So that shift, if you like, is it stylistic? It is, because it's about the technology that it is working on, but also the simplification of what it was. We are at the moment in time now, where things have to be quick, efficient, clean, simple. And I think that that particular change epitomizes that particular set of values.

Jenifer: I think one other interesting thing we noticed as we were looking at this space is that most of the performance or optimization updates that were made were within the tech space.

Which is maybe the space that you would have thought had already been working on their identities to be quite optimized, because they were within the tech and digital space largely. Such as Adobe. So they may be kind of, like, a few steps ahead already of many other identities. So it might be some… a place where they're already ahead of the curve, and we might be seeing them kind of, again, kind of leapfrogging from others, and really pulling other identities along with them. So, you know, ahead of the curve and pulling others ahead with them, it might be a trend that we're seeing looking forward. So, a poll for all of you. How effective do you feel that your organization's current brand identity is? Is it not? Is it more so just on special occasions, or in certain moments, or is it… yes.

Lee: There's so many reasons why you would change, some big, some small. Strong recommendation is if you want to avoid a gap. Cracker Barrel, the identity should never, ever be the story. The reason for change should be the story. So… how are we doing on our polls? .

Lee: Pretty good, so the majority feel it's brand is quite strong. There's a couple in the performance area there as well, I thought, could sing.

Jenifer: Tale of two worlds, either dated or it's working quite well.

Lee: So designing for survival, then. So, if we agree that, you know, brands, you know, a GE always continually needs to be thinking about this. We've been doing this for 80 years, so we think we're pretty good at this. However, there are designers that are better, so we're going to just look at one that is better than us. And that is nature. Who's been doing this than we have. So, here, she's created an opportunity, so we could think of this as a marketplace, if you like.

Grass. There's many creatures that have been designed to take advantage of this opportunity, so if we look at one of one of those. It's a deer. And our deer here has been honed and hoofed sort of in that crucible of evolution for millions of years. It's a super simple design, with a number of variations. Perfectly adapted to survive. Trial and error, test and learn. It's successful, needs a speedy frame, warm coat, multi-valve stomach. For digesting grass. It's got lateral eyes for seeing predators coming. All its organs are optimally positioned. Nothing is wasted, everything's optimized, processed engineered, it's super efficient and simple, if you can call any business or simple. It is simple.

However, why, then does it have these things on its head. They're heavy. They're not particularly practical, even for fighting, they're not particularly practical, or protection, they're not particularly practical. Their difficult to maintain. They're unwieldy, they require a lot of energy to… it’s difficult for eating, even. They aren't simple at all. However, you know, they are the reason why that creature is the success that it is. I mean, it brands it, it carries a message, it says…

Do you want some? Now, it's saying that to rivals, predators, potential mate. And that message has an experience to match the rhetoric, but essentially, it is a message. And as I say. That's not essential. Horses don't have those, they have sort of flowy, tail things that they're showing off.

So, that model, then, that our simple Business model of a… a deer, antelope, bovine, is basic. And then it has been amplified Across many continents, and varieties, with a variety of headgear, because if you don't like tree branches sticking out of your head, then you might go for something more a corkscrew, or perhaps bottle opener, or some other vicious-looking Swords on the back, then.

And the point about this is that this amplification on a simple model. This extraordinary appendage, or way of appearing, is repeated ad nauseam across the natural landscape. So, here we've got some pretty good ears to write home about, or we can have patterns. We can have spots, It's a beautiful color. There's movement, There's shape, there's scent. There's sounds, and sound with a good haircut always goes together, every pop star knows that.

There's also, you know, different finishes. You can have a nice metallic finish. Perhaps you want to go for more luminescence or fluorescence. Even the humble pigeon uses iridescence with a combination of other things, right? Sort of patterns and different motifs to stand out. So, when you look at these guys, they're all doing it in order to be their best selves, to succeed, to survive, and to exist beyond themselves. So, when you look at this, you then think, you know, is my brand actually really working hard enough? And the thing about organizations, and if we think about our deer on the left-hand side here, as a professional services brand, or a bank, or a technology brand. Your questions around simplicity, functionality, utility, performance, they're usually pretty easy arguments to win from a marketing perspective, brand perspective.

The amplification argument, so we're gonna have horns, and we're gonna have uniqueness, so that we stand out. Generally is a much, much harder argument to win, even though the legal department will be saying, actually, we need to register this, it has to be, it has to be unique. It's still a very tough ask, despite the fact that most business strategy is copyable. You know, your cost control, your technology integration, your people growth strategy. The logistics, they're all essential, but they'll pretty much be very similar across lots of the same sorts of brands. So you do need to get them right. But that differentiator, that thing that's going to make the business compete and win, your competitive advantage, all businesses know that they need to have one. However, when you look across So many brands today. They don't have that. They don't have that characteristics. And it's the difference between If you like, something that works, and something that is winning.

Other thing about this is if you are not taking these risks, with your brand, then you're putting yourself at a massive disadvantage. And I kind of hear how people say, well, actually, surely that's always been the case of brand. It's always talked about the fact that they needed to be differentiated, and they need to stand out. But what is important now is that it's not just your core identity, but everything about you needs to have that advantage to it and there is a massive risk if you don't do that, which we've already talked about. Jenifer, I don't know if you want to pick the story up again?

Jenifer: Yeah, I think kick it off with the quote.

Lee: That I think sums up really well, from Mark Zuckerberg.

Jenifer: But the biggest risk is not taking any risk. In a world that is changing really quickly, the only strategy that is guaranteed to fail is not taking risks. And we see the world is full of iconic identities that began as uncomfortable leaps. And it's not leaps of faith, it's strategic risks. And, there's many, many examples that we've called out that, every one of these examples began with a pushback at first. And it's not that they were wrong, they were just early. They just were showing something that was quite new, such as Apple. When Apple came out with its name and its identity, it was considered really off. Many quotes from, you know, businesses to journals, saw it as, you know, something that felt, you know, really playful, inappropriate for computing. It thought it would limit its appeal, it wasn't serious enough. But it ended up taking off, and it ended up being bigger than, you know, just computing. It started personal computing because it actually had appeal to schools and to people. It opened up kind of a whole new world that was unexpected by this name. That made it feel much more approachable, and something that people could invite into their homes.

To Nike, where, you know, I think this is a famous quote, but from Phil Knight, who said, I don't love it, but let's stick it on the shoes and see what happens. They took a strategic risk. The logo itself kind of looks like a checkmark, but inherent within it is this kind of beautiful motion, and in itself, it's used without the name very often, and used in so many transformative ways. That's really taken off, and it's so iconic today.

To T-Mobile. Back when it was released, brands did not use pink in 2001. It's kind of hard to imagine that. But back then, it was just a color that was not touched. And many, many publications and people back then said something like, it's a risky move, asking customers to trust a carrier that dresses like a nightclub.

But since then, you see this color, you immediately know it's T-Mobile. And they are quite, precious about this color now. It's trademarked, no one else can even come close to this color, or they will come after you. It is a precious asset to them to someone like MTV. They're kind of the originators of this flexed visual identity, but when it was released, there had really been nothing like it. And executives felt really uncomfortable about it, like, how are we gonna trademark this? We're gonna have to trademark every single version.

And they felt like it needed to be something that was consistent and iconic, like the CBS Eye. But the teams really fought for it, because this is something that, for the culture and for everyone watching it, it needed to be something that was living. And, you know, as we know today, it's something that lived on and was just so appropriate and so MTV.

To Starbucks. If you've seen the original logo that has evolved into this version, she was odd, almost confrontational. A coffee brand with a topless mermaid was not subtle. The idea that Starbucks would select an icon that was based on, a siren that's calling sailors to their death, is quite risky. The idea that you would choose that as your symbol, is quite brave and unusual, but it immediately gives your brand a lore and a story, something to build in. Beyond something that's abstract that you have to work to build meaning into. So a risk, but, so iconic. And something that has an immediate story of the lure of coffee, immediately built in.

So, another question, just to think of yourself, does your organization promote a culture of risk-taking? Are we open to strategic design risks, and do we promote more space for risk? A question for us all, just as we think about this, is your organization using its expression with enough bravery? Is the answer no? Is it just on those special occasions or in certain moments? Or is the answer yes? I think back to that, that previous, idea.

Are we opening ourselves up to enough risk-taking and promoting a culture of risk-taking. As we were doing research on this, it was interesting, because we're certainly not the only brand is not the only area that deals with this, looking into just the idea of risk-taking. There was a recent article in the Harvard Business School where surgeons are so inclined to standard operating procedures that they are less likely to look for new solutions to medical problems.

Which is preventing life-saving breakthroughs from emerging for patients. And they're trying to figure out how do we how do we fight that risk adversity. It's just ingrained in so many places. It's how do we encourage that risk-taking and that space for risk-taking. So, let's see how that predominantly, we're falling into the bucket of less bravery being taken, or it's more on those special occasions.

Lee: Waiting for Christmas.

Okay. Of course, then the question is, okay, so how do you get risk-taking. When you're looking at these topics, principles that we work to that would be worth just running through. And the first one is perhaps really obvious, but whatever you do, you need to build it from… an authentic, Truth of an organization. The question is, it can be hard to find out what that authentic truth is. Customer and stakeholders are, obviously, really key inputs. You need to understand what they think. But they shouldn't be deciding what your brand is, absolutely not. The brand should be this embodiment of an organization And therefore, needs to be authentic to itself, not to audiences. And for this, you need to understand and have insight into exactly what is the core of the organization. What makes it tick? What's its purpose? Why did it get set up in the first place? What is… what is the things that really are part of its DNA? So, for example, Swarovski had early technology to make beautiful crystals, long associated with Hollywood. But was losing touch with, younger audiences, because it had begun to adopt the luxury cues from the high-end jewelry. Kind of getting a bit ahead of itself. So, sort of white, stark, cold, and as a result, he was becoming increasingly kitsch, not cool.

And the difference between kitsch and cool is a subtle one. So, the idea that we worked with them on was called the Wonderland of Expression, which is actually to go back to the core of what they do, which is a product that helps you express yourself in, in very special moments. So, words like dazzle, strut, show off, would be okay words for this brand. Giovanni Engelberg was appointed the head of product design to kind of supercharge that, you know, a particular part of the product range. And we brought in a rich color into that brand to bring up the volume.

And change the granny swan, if you like something you might find in your grandma's lounge to become that much more cheeky marks one. And we also tweaked and dialed up the Swarovski logo so it's used big in most situations. And with the visual system turning the packaging into a stage for the product to perform on. And with that, the whole feel of it becomes much more… show business, and that's not about spending more money, it's about more, it's extra, it's bringing the extra out in you. The results of this was 10% increase in sales the year after, 13% increase in the retail sales, 5% online, and actually, importantly, and bizarrely enough, 3% increased in their B2B sales as a reflective glory from new sense of self.

Jenifer: The next principle is making decisions strategically, not subjectively, which again may, seem, clear or obvious, but it's something that can be tricky. And this is, you know, making… trying to avoid those cases where we hear things like.

I hate yellow, or my spouse, didn't like this direction. It's making the case in a really strategic way that avoids. The personal taste lens, and ensures the design process is really seen through that strategic lens. And Bombardier was a case for really setting up the story, the rationale, and the decision in a really strategic way, so it was really structured, and the case was made in a really logical way that led to a really successful outcome. So, in Bombardier's case, they were evolving from, utilitarian manufacturer of aircraft. Into an innovative, pure-play aviation, manufacturer, or aviation leader, more for, kind of, private aircraft, for, business leaders. And so, with that, they needed a new brand that really helped shift the perception of who they were creating this aircraft for that would signal a successful transformation to the world.

So, this was the identity that was created, and it was quite transformational, and that degree of change, making a big transition, was a strategic decision that was made. Not to take a small step, but to make a big leap as far as the degree of change. So that the perception of change was quite dramatic, that people would see them in a very new light, that it appear very different from peers within this space, so that they were seen as, you know, luxury but welcoming. That people saw them as a very new Bombardier. And the market really responded. The stock jumped after lunch, and it was what they credited to as a lot to do with the brand. As analysts really saw Bombardier as, being very future-focused, and seeing the transition being behind them, that they were really focused on being that pure-play aviation leader going forward.

Lee: What I really like about this as well is the story of the mark, is that the Bombardier aircraft break… the first aircraft to break the sound barrier, and the photograph that was taken by NASA. Of what happened in that moment. And using that as the symbol.

Jenifer: The symbol of their innovative.

Lee: The next principle is you've got to get the CO. Or the decision maker to own it. It's their tool to help them transform. And to move where they need to move. I mean, of course, the design needs to see a, you know, broad external, internal insight, but it should never be a workshop exercise. Brand is the tool to focus and drive the business strategy forward, and the CEO owns the strategy. The brand is his tool to control that narrative. So, getting him on board, paramount.

In this case, Nokia. Nokia was in the pockets of over a billion people. But they hadn't made a phone since 2013. Nokia had, in that time, transformed into a leading B2B network technology provider. However, if you went to Google and you looked up Nokia, you would get just lots of pictures of Nokia 310s. So, most people had continued to see Nokia as this mobile phone company, and part of the perception was reinforced by their iconic 1967 bold Geometric microgrammer logo, which we all know. Which beautifully reflected its durable phones, yet doesn't say Innovative Technology Leader. So, the first thing we were looking to do is to change that. But, we also wanted to take Nokia's 150 years of change and innovation and go forward with that.

So the linkage to Nokia's history, innovation, was that underlying geometry that the microgrammer and its angular form, and building in that into a much lighter, faster, more technology-looking logotype. The third thing was to take Pekka's purpose, creating technology to help the world act together. So, as you can see, each of the letters. Works with its neighbors to complete the visual meaning. Of course, also reflects the fact that Nokia's technology is invisible most of the time. So this visual trick, the sort of one letter needing in others, absolutely plays to Nokia's idea of collaboration. They're a very easy company to partner with. And of course, a new world of technology is all about the interaction of one industry.

The visual system also was picked up on that, and the idea that Nokia was there, was in the background, was making things happen, and the fact that elements could work with the identity was a key part of establishing really what they were about. After the launch, Nokia's share price went up 3 points, but more importantly, 89% of external coverage was actually recognizing Nokia's new strategy. Now, here's the kicker. Nokia actually hadn't changed their strategy. It had been their strategy for 3 years. So, doing this gave them that reappraisal that they needed for their B2B audiences. Then, again, internally, it helped Pekka supercharge his internal change agenda. 88% of the internal audiences said they were prouder to work for Nokia now. Because their identity now matched what they thought of themselves.

Jenifer: I think that's a nice flow into this one, and recognizing, I think we have 10 minutes, I'm going to speed through this case, because I want to have some time for some Q&A. If there's any questions, but the fourth point is narrating why to turn skepticism into support, and this one is just so important. And I think back to some of the examples we gave up front of those cases that backfired, and they went back to the old logo, like Gap and Cracker Barrel. It goes back to this case, more than it doesn't, because the story wasn't there, the rationale wasn't there, and people didn't understand why the change happened.

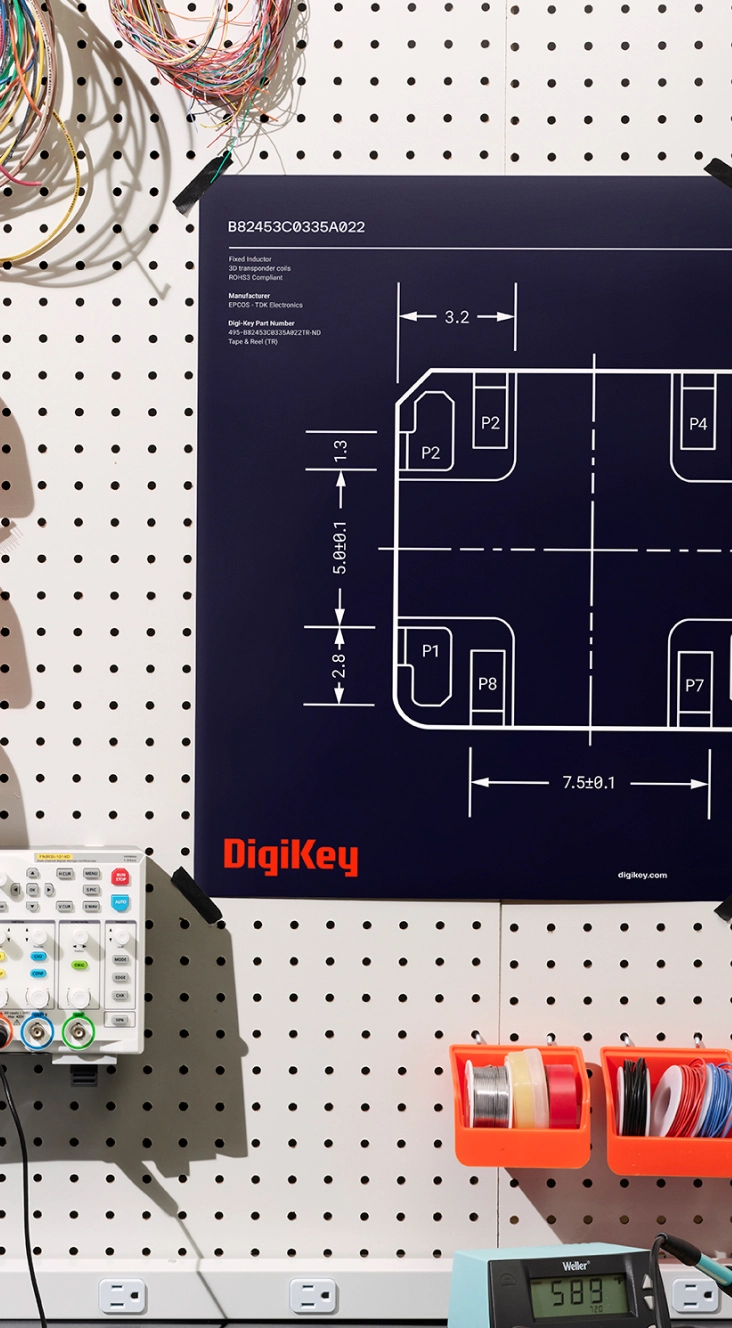

And a case where, you know, I think the rationale had to be there was Digikey. It was such a beloved brand, many people, I'm sure, haven't heard of it, but… if you're a Digikey lover, it's a bit of a cult brand, you've heard of it, and you love it. But they're basically the Amazon of electronics and technology part. Apple R&D, SpaceX R&D, order parts from them. My dad, who was a hobbyist, orders parts for them. When we were working on it, he said, don't F it up. But they are just so beloved, both by employees and the people, that buy parts from them. So, to work on a brand that is so beloved, you have to take such great care with it, and bring teams along for why you're changing it.

Because when we were doing research, only 13% of employees thought there was any need for change, to meet the growth goals that were set ahead of them. So, what we did was evolve with a lot of care, and taking into consideration all of the people that loved them. We took ahead the best parts of DigiKey, and actually built in a part of that love for the brand into the story. The idea of the system was, in your language. Really taking all the language of engineers and designers to build the system, building it off the parts, that they work with, keeping the logo, but just modernizing it, and building a language around theirs. And then bringing it to life for employees, for events, and for, you know, people that work with the materials in a really rich way that everyone got really excited about, and they felt that connective thread.

Lee: Last one, do this super quickly. We've already said this, but you need to make sure that the identity isn't the story. Now, Norton's case. This logo dates from 1913, with a few minor changes.

Their problem, extremely passionate, a bit like DigiKey, the sort of die-hard fans, but unfortunately, die-hard fans were also beginning to die out. So the brand has nearly collapsed a number of times. They've been working on a new range of bikes, the Max family, which are super bikes, and then the Atlas family that are adventure bikes.

What we wanted to do was to update the identity to match the update of the product, so that when you saw the product, yes, it had taken qualities from that original mark, the thicks and thins, the rather quirky little hat on the end, the overline to the identity. You could see where it had come from, like, you can see where the bikes had come from. But nobody was then talking about that. They were all talking about the new bike range, and the fact that this sat on it, it just went with it. So the meaningful conversations become actually, the products not the story of the logo. The story of the logo is just the full stop to the transformation. Lastly, and very quickly, kind of our design equation is thus. You need to find the truth. Strategy, insight. Yes, you look outside, but really, you're looking to unlock the brand's DNA within, the reason for being the mission. And then to simplify that down, make it, hone it, sharpen it, make it work. Our basic deer model. So it can perform wherever it needs to show up, not just the, you know, the logo bits, but all of it, how it performs in its context.

And then, most important, you need to give yourself a competitive advantage. What does that mean? It means you've got to connect emotionally. To connect emotionally, you need to take risk, because nobody is going to tell you to take that risk from the outside. People don't like change. But you need to do it. You need to feel part of it, because anything but a risk is probably the most risky thing you can ever possibly do. Any how do you measure identity effectiveness? Do you want to do that one, Jenifer?

Jenifer: Well, I think there's a few ways. I mean, you can, we do brand trackers, where we can track both externally and internally how the brand is doing. Like, what you were noting, Lee, we can track, like, how it's doing from a stock perspective. We can track how, you know, employees are reacting to the change. So, there's different factors that we can track on, and usually when we're starting a, you know, a project, we'll align on what are some of the… what are some of the key, you know, factors that we want to see lift on, and align on those, and begin, you know. Setting those as the things that we want to track going forward. So that we know what we want to see the movement on going forward.

Lee: why is amplification a harder sell than simplification? I think it is because it does involve risk. You can pretty much justify a simplification. It's, in a way, it's self-evident. I think the amplification gets into the areas that we're talking about, right? Like, do I like it? Don't I like it? Is this gonna work? Isn't it gonna work? I think it's always important to remember that not everyone has to like it. In fact, if it's any good, not everyone will like it. You don't even need everyone in your market to like it. I mean, you know a third of the market is a big piece to win. So, it's one of those things where, really, it's a case of having to think through, actually, well, what if we don't do this, what is gonna happen? We're gonna be ignored. We're always gonna be struggling. We're always gonna have to come up with some… product feature, or price drop, or something else that's going to make the difference, versus riding on a wave of goodwill, because people like you. Because they connect with you emotionally.

Jenifer: Next question. How can brands prepare their internal teams and stakeholders for potentially polarizing design changes?

Lee: I think this goes to the story. You have to get the story right that surrounds it, and if you do that. People may not like it, may not agree with it, but they'll understand it. And understanding is the first step to acceptance. So get that story right. And you've got half a chance of winning that argument. Question 4 is a great question. What are the key differences in developing B2B, brand versus B2B B2C? We have found out over the years that brand in B2B is actually more important than it is in B2C. Why? Because you're willing to take a risk in your own personal life. Where you're not prepared to take big risks, your B2B decisions, because there's more riding on it. Your career, for example, Company, for example. So… B2B… Can be trickier in that sense. Tends to also be that the marketing in general. Familiarity with the, sort of, that world of storytelling is usually more alien in a B2B world. It tends to be more rational. Jenifer, is there anything you've particularly observed there?

Jenifer: Yeah, I think within that space, we definitely see bigger risks, what we would say, within the B2C space than B2B, but I do think we are seeing bigger and bigger risk within B2B than we did 10, 15 years ago. As, as brands are really looking to, find greater distinction and separate themselves, and feel like they can have, you know, greater character, in how they tell their story. So, I think we will see greater risk-taking in B2B in the future. But it's still an emerging space, and I think that's one of the distinctions, is there's just been greater risk-taking in B2C.

Lee: So, yeah, I think that's right. And the last… so the last one we take… so, simplification versus amplification, essentially the same as form and function? No, it's not. It's absolutely not and full form and function, of course, plays a part. But what the amplification is… you are looking for exaggeration. You are looking for… Something that is, demonstrable. Versus form and function, which, you know, in our motorcycle example is, yeah, that thing is designed in a wind tunnel to go as fast as it can. But you put everything in a wind tunnel, it would all look the same. So it's not the same, and I think that is actually is a misconception around, a lot of design, actually. I think it needs to work harder than that. Actually, I don't know if you agree with that, Jenifer, we've not.

Jenifer: Yeah, no.

Laura: We're at time, so everyone, thank you for, attending. If we didn't get to your questions, please feel free to follow up, with us directly, and the recording of this will be available after this episode. So, thank you all.

Lee: Thank you.